[portfolio_slideshow id=2388]

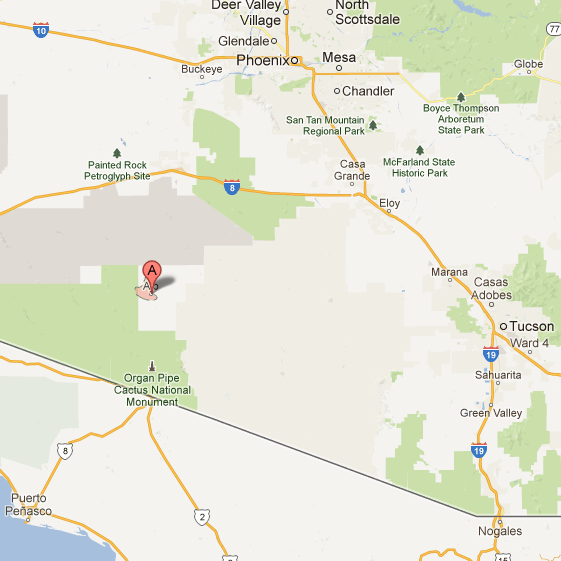

“You guys sure picked a busy day to come out here,” said Lt. Bill Clements, commander of a remote Pima County Sheriff’s Department substation in the sun-blasted Sonoran desert about 140 miles west of Tucson.

On a recent morning, Clements sent deputies into the desert to recover still another body — the fifth in five days. Hours later, back at the station, a deputy unzipped a white body bag, revealing the corpse of a man who had died making the brutal crossing, his lips shrunken either with dehydration or from partly being eaten by wild animals — perhaps coyotes.

The Ajo district recovered 18 bodies last year. There have already been eight this year, and the summer sun is still a month away.

Out here, life expires in a blink — suddenly and without dignity.

These are the facts of existence here, two hours out of Tucson, where pitchforked cactuses dot the horizon and blue hangs in the sky like a canopy. Here, national drug and immigration policies meet desperation, and tensions play out in this small hot town. Deputies here act as the tip of the sword.

Life for officers in Ajo is a grinding routine of boredom broken by blasts of grotesque reality.

In the same city where the lead item in the local newspaper’s police blotter one day was “Loud noises heard; unable to locate,” harsher reality always intrudes: Drug seizures — the average marijuana load seized in a stop is 300 pounds — domestic violence, arson and methamphetamine addictions all are part of the deputies’ job.

And, of course, the bodies in the desert.

The sheriff’s department in the Ajo District operates as a kind of self-sufficient outpost of the big county sheriff’s department in far-off Tucson.

Most shifts are covered by four staff members — two deputies, a corrections officer for the 21-bed jail, and a 911 dispatcher — who are responsible for a 3,000-square mile, heavily drug-trafficked corridor in the brutal stretch of terrain between the Arizona-Mexico border and Phoenix, 110 miles to the northeast.

In this district, the Pima County Sheriff’s Department collaborates with federal agencies like the Border Patrol, Customs and Border Protection and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. The alliance of agencies is called the Border Anti-Narcotics Network.

The network made 440 drug seizures in this fiscal year’s first quarter, netting 18,000 pounds of marijuana, according to Clements. That’s up 2,500 pounds from the first quarter of last year.

Clements attributed that to “increased technology and more officers in the field.”

Still, he said, there is no way to know how many illegal drug shipments are making their way northward, undetected.

What does a cop have to do to end up in a place like this?

Pima County Sheriff’s deputies responding to a domestic disturbance call in Ajo. Because the deputies live in the town of 2,500 people, it is difficult to build rapport, knowing they might have to arrest a neighbor. Alex Wroblewski | NYT Institute

Some deputies out of the police academy, eager to make their marks and ascend department ranks, agree to serve three years in Ajo. Most leave after their required stint expires.

Back in Tucson, a deputy who chose to put in his time at the desert outpost joked that he did so without realizing exactly what he’d signed up for.

“Nobody told me I wasn’t supposed to check the box,” said Deputy Jesus Bañuelos, who served three years in Ajo before becoming a spokesman for the sheriff’s department.

Despite its drawbacks, serving in Ajo is a sort of rite of passage for young officers. Because of the small staff, officers often work their cases from beginning to end — making arrests, filing cases with the district attorney and presenting facts to the grand jury if needed, Bañuelos added.

The primary responsibility for the deputies is to cover the community — usually sticking to town unless called by Border Patrol or any other federal agencies operating in the area.

Ajo, an old copper mining town, has about 2,500 residents. A green tint runs down the mounded rock at the edge of town, a vestige of the mine, which closed in 1986.

“There’s no industry here,” said Deputy Brad Gill, adding that law enforcement agencies keep the community afloat. “This is a government town.”

Spanish colonial architecture rings the Ajo plaza. Throughout the town, tidy Southwestern-style homes share a block with dilapidated ranch houses — some of which, deputies suspect, could be active drug spots.

Small-town sensibilities mean knowing that the individuals whom deputies bust for heroin today might well stand next to them in church tomorrow, Gill noted. He added that it is hard to build rapport with the community if people assume the officers will soon move on, leaving Ajo and its problems behind.

Since April, a serial arsonist has lit three separate fires in town.

Officers speculate that the fires could be drug related. A fire requires all deputies on duty to respond, creating a possible diversion for drug shipments to move unimpeded through town. Posters at local business offer $2,500 for information leading to an arrest.

But officers said that despite its isolation, working in the Ajo District has its advantages.

“I like the freedom of working out here,” said Deputy Andrew Fletcher, 28, who has served two years in Ajo.

“You see things you’d never see anywhere else.”

Fletcher said that just last week he had stopped a man carrying 75 pounds of marijuana in his backpack.

Recently, accompanied by a reporter and a photographer on a blazing hot day, Fletcher drove his truck down the rough dirt road straddling the border 40 miles from town.

Two miles from the small border checkpoint, a high pedestrian fence drops to a short cattle fence. Farther down, there is no fence at all separating Mexico from the United States.

It’s easy to cross the border here, if you don’t know what lies ahead.

Fletcher pointed to an empty black water jug, probably left behind by a migrant heading north.

“Those must be standard-issue in Mexico,” he said. “They use black jugs because the clear ones reflect sunlight.”

That could give away a migrant’s position, he said.

So far this year, the department has apprehended 257 undocumented immigrants a 38-person increase from 2012 at this time, according to department numbers.

A border-length fence might help to deter illegal crossers, Fletcher suggested. “But it’s just like anything else. You solve one problem and people are going to find another way around it.”

Discovering human remains is a regular part Fletcher’s job. He estimated that he has seen over 100 dead bodies since he started working in Ajo. His boss, Lt. Clements, said that he himself had encountered 300 to 400 bodies.

Sometimes, Fletcher said, deputies come across migrants who have gone mad with dehydration, walking in circles or making “snow angels in the sand.”

That morning, while deputies traveled south toward the border to retrieve a body, a migrant scrambled out of the brush, asking for help. His eyes were bloodshot, and he was drinking his own urine from a bottle — he had seen that in a television show, one deputy said.

And sometimes, Deputy Gill added, “They quit and just walk down the highway. They’ll get picked up and brought back to Mexico and try again another day.”

While a recent report by the U.S. Border Patrol indicated that the number of immigrant apprehensions has fallen sharply since its peak in 2000, Gill is unconvinced that the situation is improving.

“All I know is that people are still coming, people are still dying, and Border Patrol is busier than ever,” he said.

On patrol, Gill parked his truck near the fringe of town, looking for routine infractions: speeding, a vehicle whose windows were too darkly tinted, a too-noisy muffler, fuzzy dice blocking the view from a rear-view mirror.

Car after car, he stopped traffic, and used his discretion when dealing with person after person.

“Tickets are a method of correcting behavior,” said Gill. “If I’m convinced someone is going to slow down, I’ll let them off with a warning” about speeding, he said.

“I’m looking for the real criminals,” he said. “I’m looking for the drugs.”

But when it comes to immigration, Gill said, he has no authority to use discretion.

In Pima County, the passage of the hotly debated SB 1070 — commonly referred to as the “Show me your papers law” — had little effect on the way deputies do police work, Gill said.

“As a law enforcement officer, it didn’t change how I do my job,” he said, adding that he uses “good police work” to establish a probable cause.

If an individual is wearing multiple layers of clothing or carrying a backpack, or is dirty from trekking across the desert, the person may be worth a second look, he said.

“All of that adds up to a kind of profiling, but there’s value to that,” he admitted. “Profiling is a dirty word. People assume that when I’m profiling, I’m making a judgment. But I’m not judging them. I’m doing my job efficiently.”

Gill said he does not actively seek undocumented immigrants, and he detains them only if he comes into direct contact with them. Often, he said, he feels sympathy toward migrants who come north to work.

“It’s hard,” he said. “I stop these guys and they pull out their wallets. I see the pictures of their kids and I think about my own kids. I realize I’d probably do the exact same thing if the situation was reversed.”

During the Institute, students are working journalists supervised by reporters and editors from The New York Times and The Boston Globe. Opportunities for students include reporting, copy editing, photography, Web production, print and Web design, and video journalism. Institute graduates now work at major news organizations, including The Associated Press, The Los Angeles Times, The Washington Post and The New York Times itself, and dozens of midsize news organizations.

During the Institute, students are working journalists supervised by reporters and editors from The New York Times and The Boston Globe. Opportunities for students include reporting, copy editing, photography, Web production, print and Web design, and video journalism. Institute graduates now work at major news organizations, including The Associated Press, The Los Angeles Times, The Washington Post and The New York Times itself, and dozens of midsize news organizations.

Son of a gun—-Good moorise cop combo!