[portfolio_slideshow id=1431]

The white van pulls to a slow stop in the middle of a road.

The driver, Betsy Shaw, turns and asks, “Do you know why I stopped here?”

Silence.

“Because we don’t have an active tower and that’s the runway,” she said, pointing to an isolated strip of road in the 1,200 acres of Pinal Air Park.

“I’m checking for planes.”

Hundreds of commercial and private planes are flown onto this runway every year, but most do not carry passengers. They are flown to the airfield to be repaired or overhauled. Others are simply grounded for months on end, casualties of the budget cuts airlines have made since 2008.

Some of the planes that land here are headed for a much more ominous fate — the “end-of-life” service provided by Marana Aerospace Solutions, the company in charge of the site.

The process is exactly what it sounds like: The planes, Boeing 747s or Airbus A 318s among them, are marked with a red “X” on their noses and stripped of their metal and valuable parts.

“Once all components are sold, the haul is bunched up to pieces this small,” Shaw said, forming a circle with her index finger and thumb. “Then they are melted down and repurposed.”

Their bodies will be disassembled and individual parts sold to other air industry merchants. At some point, Shaw said, the parts become worth more than the actual plane.

Two years ago, Relativity Capital LLC purchased the airfield, which was initially built as a World War II army base. The company turned the site into a stand-alone maintenance, repair and overhaul business under the new name of Marana Aerospace Solutions.

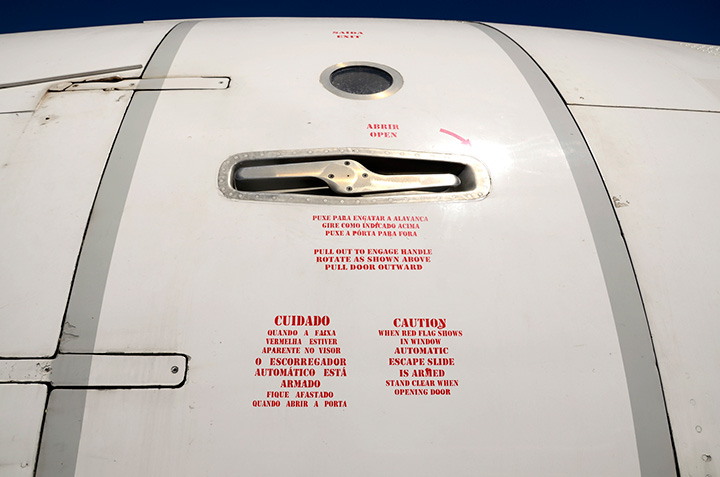

Warnings are printed in different languages on the rusting door of a Boeing 737 in the storage area of Marana Aerospace Solutions in Marana, Ariz. Rattlesnakes, bees and other wildlife can be found living inside airplane components that are left open. Anibal Ortiz | NYT Institute

On a scorching day in the Arizona sun, all of the commercial planes in the fleet undergo a process the Marana employees call “venting.”

When the temperature hits 90 degrees and above, the doors of all the planes are opened to let air in and prevent the plastic inside the planes from melting. At the end of the day, a small crew of no more than six staff members is given the task of closing the doors to the hundreds of commercial airplanes in the fleet.

Grounded Boeing 737s, as well as regional jets by Embraer and Bombardier, can be found on other areas of the site.

There’s even an Airbus A 330 in the air hangar getting a paint job and sheet metal work done.

Some of the aircraft have aluminum covers over their cowlings, designating they have had their engines removed.

Once they are ready for flight again, they will receive a new engine and undergo inspections by the Federal Aviation Administration to ensure they are safe to fly.

But these, some may say, are the lucky ones.

These planes will one day get new engines, and be able to take off down the runway — an opportunity not shared by those with a red “X.”

CORRECTION: This post has been updated to correct the name of the Federal Aviation Administration and to correct that Marana Aerospace is at Pinal Air Park, not Evergreen Air Center. The article and an accompanying photo caption also gave incorrect information on what happens to some of the planes. Their wings are not replaced, and the skin is not stripped, but crushed and recycled with the rest of the plane.

During the Institute, students are working journalists supervised by reporters and editors from The New York Times and The Boston Globe. Opportunities for students include reporting, copy editing, photography, Web production, print and Web design, and video journalism. Institute graduates now work at major news organizations, including The Associated Press, The Los Angeles Times, The Washington Post and The New York Times itself, and dozens of midsize news organizations.

During the Institute, students are working journalists supervised by reporters and editors from The New York Times and The Boston Globe. Opportunities for students include reporting, copy editing, photography, Web production, print and Web design, and video journalism. Institute graduates now work at major news organizations, including The Associated Press, The Los Angeles Times, The Washington Post and The New York Times itself, and dozens of midsize news organizations.

The name of the airport is Pinal Air Park. The Facility is Marana Aerospace Solutions, Not Evergreen. The engines can be reinstalled, we do not replace the wings. The engines, avionics and more valuable components are removed as part of End-of-Life, as well as, the landing gear. The skin is not removed before being scrapped, it is part of the hull and that is what is crushed and recycled.