In the desert a mere 10 miles outside of Tucson, shooting stars streak the blackness, and the vast silky ribbon of the Milky Way can be seen.

Astronomers treasure the skies in the Tucson area, a city where a cluster of six observatories scan space for intensive scientific research, a vital part of the local economy. The people love it too – there’s a local tavern, the Sky Bar, where stargazers can see their first view of Saturn.

But the astronomers fear the stars in Tucson’s skies may soon be harder to see.

After seven years of planning and environmental studies, the proposed Rosemont Copper mine intends to break ground this year. Its new home in the Santa Rita Mountains, south of Tucson, will bring scores of floodlights to the area, potentially casting an unwanted glow to the treasured night for the next 20 years.

Rosemont Copper says it is cognizant of the dark sky, but the economic benefits of the mine are substantial. The company said it expected to generate $19 billion in revenue for Arizona over its years of operation, bringing more than 2,900 jobs. But it is all on hold until federal environmental studies are completed.

The company has hired local engineers and researchers to handle the many environmental concerns, said Jan Howard, a spokeswoman for Rosemont Copper.

“This is a billion-dollar project just to get the construction completed on it,” she said.

But astronomy is a large local industry as well, and just as the mines need their copper, the observatories need the dark.

Tim Swindle, department chair of the University of Arizona’s Lunar and Planetary Laboratory, said he worried for the future of ongoing asteroid search programs conducted by scientists at the nearby Catalina Mountain and Kitt Peak observatories — which for the past eight years NASA has cited as leaders in asteroid research.

The skies are susceptible to even the subtlest of changes, he said.

“This is relevant because you can see the discovery rate drop every year when the skies get cloudy in the summer in southern Arizona,” Swindle said in an email. “Having brighter skies would also drop the discovery rate.”

The benefit of the darkened skies in the Tucson area became clear with the recent discovery of the asteroid Bennu.

More than 500,000 asteroids roam among the planets, and among them, Bennu has especially rare properties. Within its craggy surface lie organic materials that may be key to understanding the building blocks of life on Earth.

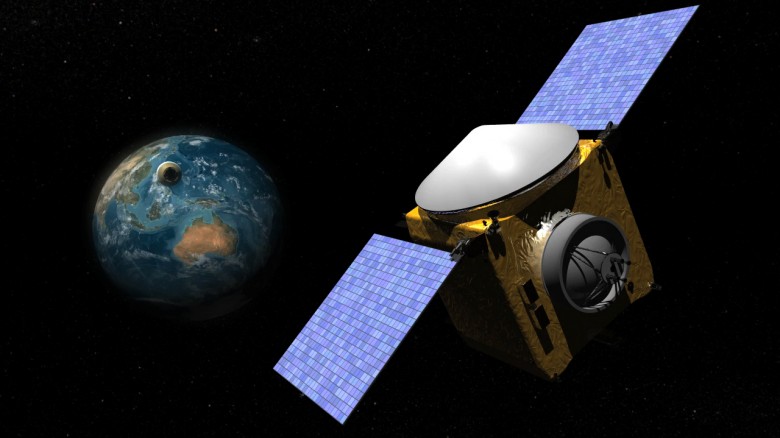

The University of Arizona in Tucson entered a partnership with NASA, which gave the go-ahead last week for the university to launch a satellite to touch down on Bennu in an operation called OSIRIS-REx, scheduled for 2016.

“Given that it’s a small, faint object, many of those studies could not have been done without the dark skies of Southern Arizona,” said Swindle.

The clear night of Tucson has long been part of local law.

The Pima County Outdoor Lighting Code mandates that outdoor lights be shielded, pointed downward, and encourages lighting designed to yield a warm orange glow, since standard white light spreads too widely. The code came about through a business and government partnership.

As in any relationship though, sometimes toes can be stepped on. The proposed Rosemont Copper site is on the other side of the Santa Rita Mountains from the Whipple Observatory, south of Tucson, and less than 50 miles from Kitt Peak National Observatory.

The lighting plan for the Rosemont mine has actually been reduced from 20 million lumens to 6 million lumens since the company first proposed its plan in 2011.

“The old plan was like adding a city the size of Nogales” to the light-pollution problem, said Scott Kardel, spokesman for the International Dark-Sky Association.

The association started in Tucson, but now has chapters as far away as Israel, Japan and Australia. In partnerships with lighting manufacturers, legislators and citizens, the group works to help minimize light pollution around the world.

“The plan proposed now is far better,” Kardel said of the mining company.

In charge of lessening the impact of Rosemont Copper’s lighting system is a local company called Monrad Engineering Inc., under contract with Rosemont Copper. The lead engineer, Christian Monrad, has been on the board of the dark sky association for 17 years. He said he was brought on to refine Rosemont’s lighting plan after its initial draft.

“We want to use as few lumens as we can, and put them where we want it, when we need it,” he said.

He said that other mining operations have since used his company’s methods, including Hycroft gold mine in Nevada.

“It’s an expansive project and our goal is to be the most dark sky-friendly mine in the state of Nevada,” said Rob Conley, an environmental engineer with Allied Nevada Gold Corp., which owns the mine.

The new lighting plan incorporates most aspects of the Pima lighting code, from warm-temperature lighting to automatic switches and downward-facing lights.

But not every aspect of the ordinance would be followed in the Rosemont plan. Some parts of the ordinance, including unshielded lamps, would in fact be impossible for any mine to adhere to, Monrad said.

Mines operate at night, when shovels in the pits “scoop rock ore and take them into 200-ton haul trucks,” he said. That work necessarily requires lights that point skyward past the horizon, which aren’t permitted in the Pima lighting code.

“We’re lifting rock 60 feet in the air to put it into a truck. The light needed to do that task, we’ve reduced it to 10 percent” of the original plan, he said.

But Pima County officials said they were especially concerned since Rosemont has not submitted a formal lighting plan to the county.

“Right now there’s no submittal that complies with the laws on our books,” said Ray Carroll, a Pima County supervisor. “There are mines that do, like Oracle Ridge mine in the Catalinas.” He has been especially vocal against the Rosemont mine for a number of environmental reasons, dark skies included.

“We’ve really had to pay close attention to the process,” he said. “Many times we feel like Rosemont is not getting the most scrutiny it should get.”

Rosemont said that it was following all regulations, but that the county had no jurisdiction over the lighting at the mine.

The Rosemont Copper mine has been under federal studies of various sorts for over seven years, according to the company website. Rosemont Copper launched a Facebook campaign called “Isn’t seven years of study enough?”

With only a handful of permits left to go before construction can begin on the mine, Howard, the spokeswoman, said that Rosemont expected to break ground before the end of the year.

Not so fast, Carroll said.

“If they get every permit that they need, there’ll be lawsuits to stop them,” he said.

For Kardel at the dark sky association, the question between having a mine or not is a false choice.

“Our position hasn’t been to oppose or approve any kind of project. It’s been to say, if you’re going to do this thing, you need to do it in the best possible way.”

During the Institute, students are working journalists supervised by reporters and editors from The New York Times and The Boston Globe. Opportunities for students include reporting, copy editing, photography, Web production, print and Web design, and video journalism. Institute graduates now work at major news organizations, including The Associated Press, The Los Angeles Times, The Washington Post and The New York Times itself, and dozens of midsize news organizations.

During the Institute, students are working journalists supervised by reporters and editors from The New York Times and The Boston Globe. Opportunities for students include reporting, copy editing, photography, Web production, print and Web design, and video journalism. Institute graduates now work at major news organizations, including The Associated Press, The Los Angeles Times, The Washington Post and The New York Times itself, and dozens of midsize news organizations.