In the desert about an hour north of Tucson, a lush rainforest presses its emerald canopy against a glass ceiling. Yards away, separated by a plastic partition, artificial waves from a million-gallon ocean creep on to the 4-foot shore. Underneath, in the “Technosphere,” concrete tunnels weave around air vents, wires and power sources to run the oversized, science fiction-like greenhouse above.

Built more than 20 years ago, Biosphere 2 was intended to replicate the planet’s ecology and sustain life for a better understanding of our world as well as the model for living outside of the original Biosphere 1 — earth.

Now, as a University of Arizona research facility, it is used to study the effects of climate change as well as other ecological projects.

But it also it serves as an educational and tourist destination.

The Biosphere 2 ocean biome contributes to understanding of the ocean community. View Larger Image Alex Wroblewski | NYT Institute

Tourists trickle down the 2.5-mile road off of state Route 77, some wondering why it exists, and others explaining to the receptionist and ticket table that they had “read all about it online.” Infamous or not, the idea of a 3.14-acre alien-like world replicating our own attracts almost 100,000 people a year.

John Adams, assistant director at the facility, said there is nothing like Biosphere 2 in scale or venture.

It’s been 20 years since the original mission; Eight researches lived in its airtight bubble for two years until the mission was aborted because of an imbalance in carbon dioxide and oxygen.

In a New York Times article from 1991, Ed Bass, the financier behind the project, was asked what he thought about using the Biosphere 2 model on Mars.

The project, Bass said, could be the model future scientists would use to create sustainable societies — or it could just be a flop.

Humankind wasn’t going to Mars, or even to the moon again, in the 1990s — let alone now.

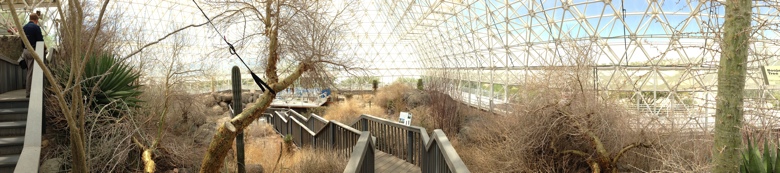

The tropical rainforest biome tests how changes in temperature affect the canopy of the rainforest. View Larger Image Alex Wroblewski | NYT Institute

When Biosphere 2 was first created, Adams said he spoke with scientists who said that attempting to recreate the natural process was a humbling experience, but that anyone who thinks they can completely recreate it is foolish.

Now, instead of a push to find an alternative to earth, one focus of the facility is testing different ways to make established cities sustainable. Since researchers are not able to “shut down half the grid” of a major metropolitan area, Adams joked, they use Biosphere 2 as a miniature city.

“We’re like a large test animal for medical research,” he said.

He described research in the facility as a “niche scientific endeavor.” With five kinds of miniature climate areas — desert, marsh, ocean, rainforest and savanna — it provides the chance to see reactions across the world.

Adams said research about earth science doesn’t really have a specific facility or way to test research like other fields of science do.

“If you look at astronomy, we have large telescopes and we put them in space,” he said. “In physics we have the Hadron Collider.”

He explained that Biosphere 2 tries to be the middle ground between controlled experiments in a traditional lab setting and experiments open to the elements in larger, natural settings, like rainforest excavations.

With all the energy put into sustaining life and the climates in the different environments of the dome, someone has to pay. The energy bill — electricity and natural gas—runs around $550,000, about half the cost when they were self-sustaining.

A view of the savanna grassland in Biosphere 2. View Larger Image Alex Wroblewski | NYT Institute

Between financing from billionaire Edward Bass, the original project funder; National Science Foundation; the university; grants; and the tickets for the tour, the bills are taken care of. Annuals costs are about $5.5 million.

But the Biosphere isn’t the end-all-be-all for understanding how the earth works and why. Even with all of the data collected, it is not representative. To attempt to balance this, researchers weigh their data against that taken outside of the dome from The National Critical Zone Observatory Program, a project that measures sustainability of the zone from soil to rock that supports life.

Even so, Adams said there is one question that keeps bringing researchers back:

“What can they do here that they can’t do anywhere else?”

Examples of experiments under the dome have been how different types of plastic disintegrate in ocean water over time. Another researcher is testing the way small changes in temperature affect the canopy of the rainforest, and soon will check how the environment works during droughts.

One of the biggest projects at the dome is Landscape Evolution Observatory, better known as the LEO project. The researchers aim to gain a better understanding for the way water moves through landscapes and how, or if, it evolves with climate change — things like how much rain from a mountaintop ends up downstream.

When the Biosphere was self-sustaining, its "lungs" prevented it from exploding as warm air applies pressure on it. Now it's an artifact of Biosphere's past. View Larger Image Alex Wroblewski | NYT Institute

What they do is take apart the traditional system of dirt, plants and other living organisms and strip it to a simpler form. Then, once they get enough information from that sample, they will add in plants to see how the water retains and reacts to the temperature changes.

“We’re putting it back together,” he said about the landscape.

Millions of pounds of dirt sit on an artificial slope — the underbelly of the oversized planter covered in thousands of sensors measuring temperatures and moisture — to replicate the mountainside.

Instead of using current soil from mountainsides in Tucson, though, the “new soil,” broken down to near-mineral form, is from northern Arizona.

When asked how new the soil was, Adams laughed.

“Geologically: It’s only 10,000 years old.”

During the Institute, students are working journalists supervised by reporters and editors from The New York Times and The Boston Globe. Opportunities for students include reporting, copy editing, photography, Web production, print and Web design, and video journalism. Institute graduates now work at major news organizations, including The Associated Press, The Los Angeles Times, The Washington Post and The New York Times itself, and dozens of midsize news organizations.

During the Institute, students are working journalists supervised by reporters and editors from The New York Times and The Boston Globe. Opportunities for students include reporting, copy editing, photography, Web production, print and Web design, and video journalism. Institute graduates now work at major news organizations, including The Associated Press, The Los Angeles Times, The Washington Post and The New York Times itself, and dozens of midsize news organizations.