Under the shade of a mesquite tree, six men stood in the parking lot of the Southside Presbyterian Church in Tucson, Ariz., waiting for someone to hire them.

The men are day laborers and members of the Southside Worker Center, a program that organizes workers and provides resources to ensure that they are safe and paid a fair wage.

The social program is one of four run by the church, including a campaign to raise funds to help bail out members in Immigration and Customs Enforcement detention — a leadership and education program — and the Migrant Trail, which has members tracing a 75-mile pathway that traverses the U.S.-Mexico border.

Southside Presbyterian’s activist roots extend 30 years back, when the pastor, the Rev. John M. Fife, made the church into a sanctuary for Salvadorans fleeing into the United States.

Those activist efforts have sometimes landed the church in trouble: In 1986, Fife was one of eight church leaders convicted of violating immigration laws for smuggling people into the United States. He retired in 2005.

For the last four years, the Rev. Alison Harrington has led the church, continuing Fife’s mission while also creating new programs like the Worker Center.

“We’re just trying to create a place where they can work under fair and just circumstances,” said Stephanie Quintana Martínez, a church volunteer, who came to the center after graduating from college in Puerto Rico.

The Southside Worker Center has begun a marketing campaign, presenting the workers as “Your local superman” and has purchased baby blue long-sleeve T-shirts, which they require the workers to wear whenever they go out on a job.

Manuel Martinez, left, 58, and Alfonso Salazar, center, are among the migrants seeking work through the Southside Worker Center. The center helps day laborers find work and attempts to protect them from unfair treatment and exploitation. Anibal Ortiz/NYT Institute

The shirts are a sign of the collective nature of the worker’s center — a bit of pride and protection from the sun and the hard labor of roofing jobs, welding and the sharp jabs of yard work in the Sonoran Desert.

“We provide a safe place for them to wait and negotiate, and provide accountability for workers in the community,” Harrington said. “Day laborers are at the end of the ladder,” she added, noting that she wants to “give them a voice and a role.”

The job’s troubles can be the least of their problems.

When Gov. Jan Brewer of Arizona signed the controversial anti-immigration law known as SB1070 in 2010, it included a provision that would have made it illegal for motorists to stop for day laborers, and for day laborers to be hired from the street.

Although that provision was part of the law that was halted by a judge in March 2013, much of the elements of SB1070 remain.

For the day laborers who belong to the Southside Presbyterian Church, this brings an element of risk each time they seek work.

“We make sure we know where they go,” said Alejandro Valenzeula, a volunteer with the worker’s center.

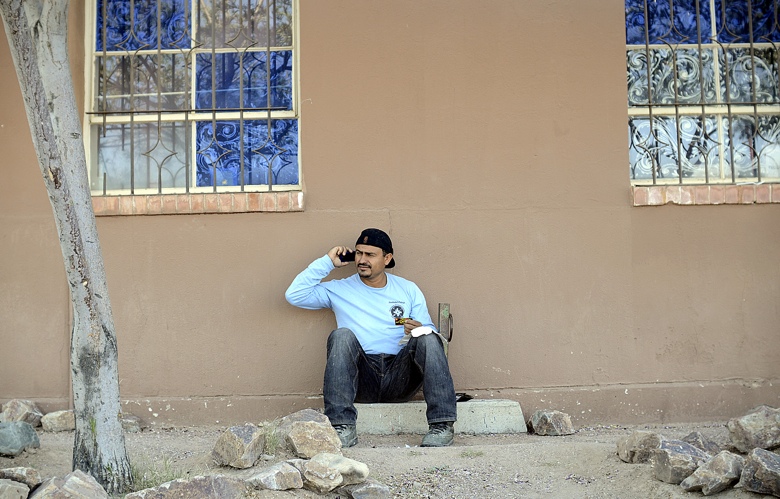

Miguel Rivera, 40, at the Southside Worker Center at Southside Presbyterian Church in Tucson, Ariz. Laborers at the center said that work has been slow for the past few months. Anibal Ortiz/NYT Institute

Quintana said: “When they don’t come back, we worry. Do the authorities have them? And many times, they do.”

The church’s efforts also extend to the courts; it is one of the plaintiffs in a major lawsuit challenging SB1070.

“We believe that our faith require us to do this,” Harrington said.

Currently, 12 members of the church and worker program are in detention; some are awaiting hearings while others are hoping to be released on bail.

One of the church’s missions is to locate its members in detention — nearly all are men — and reconnect them with their families.

“It’s really a desperate process for them,” Quintana said.

However, Quintana points out, church means are meager, and the sole connection between the family and a member in detention is often a prepaid phone card.

Meeting bail is also extraordinarily difficult for most members, as bail is at least $1,200 — although it can exceed 10 times that.

Activists in Tucson loosely tied to the Southside church have been holding a series of events to raise money, including an event called “Dinner, Movies, and Bail.”

In exchange for a $10 donation, attendees ate a dinner of enchiladas, rice and beans and watched “The Fantastic Mr. Fox” and “Goonies,” projected on a sheet in the backyard.

Miguel Gonzalez Duarte, right, 37, was released on bail with help from the Southside Presbyterian Church in Tucson, Ariz. The church community works to help residents without proper documentation better inform themselves, find work and bail them out of detention centers. Anibal Ortiz/NYT Institute

The catch was meager: $120 for bail money.

A car wash gathered $420 for bail, and community members and volunteers are contemplating other events.

The fund-raising goal is $10,000, enough to get a few members out of holding centers around Arizona, including the Florence Staging Facility, miles north — where 7,650 people were in custody between November and December 2012, according to information from Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse (TRAC), a nonpartisan research project supported by Syracuse University.

Right now, the fund has raised roughly $7,500 — enough, certainly, to get at least one member out of detention.

Miguel Gonzalez Duarte, a worker who was detained by Immigration and Customs Enforcement after a traffic stop, has posted bail through the fund.

“We don’t get these victories very often,” said Raúl Alcaraz Ochoa, a coordinator at the Southside Worker Center. “It’s the same problem. The police aren’t using their discretion, they’re just grabbing people up.”

“We see a lot of fear,” Harrington said of the members. “We see police calling the Border Patrol when they don’t need to.”

According to data from TRAC, nearly 1,500 individuals in the United States are taken into custody each day by Immigration and Customs Enforcement, but only about 25 percent can post bail.

On May 29, Quintana and another supporter drove to the Florence Staging Facility to retrieve Gonzalez.

Upon returning, they said they would celebrate with a party at the center.

The next morning, more workers will go out to the parking lot, clad in their blue shirts, and wait for work.

During the Institute, students are working journalists supervised by reporters and editors from The New York Times and The Boston Globe. Opportunities for students include reporting, copy editing, photography, Web production, print and Web design, and video journalism. Institute graduates now work at major news organizations, including The Associated Press, The Los Angeles Times, The Washington Post and The New York Times itself, and dozens of midsize news organizations.

During the Institute, students are working journalists supervised by reporters and editors from The New York Times and The Boston Globe. Opportunities for students include reporting, copy editing, photography, Web production, print and Web design, and video journalism. Institute graduates now work at major news organizations, including The Associated Press, The Los Angeles Times, The Washington Post and The New York Times itself, and dozens of midsize news organizations.