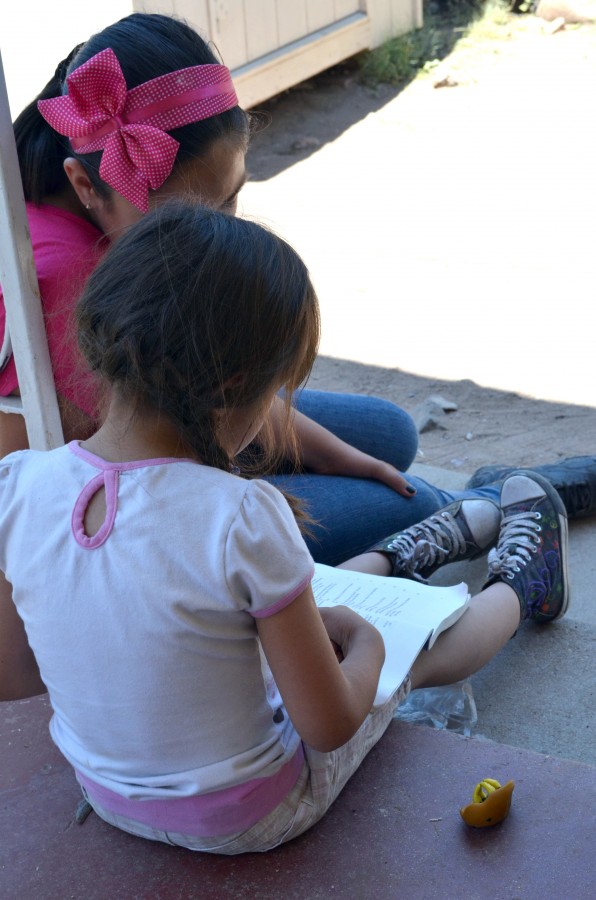

Children all over the U.S. are struggling to cope with immigration issues that directly affect their families and their lives. Danya P. Hernández | NYT Institute

In the small town of Nogales, Ariz., about an hour south of Tucson, Roman and Giovanna prepare for their weekly trip into Mexico. Although they live less than a mile away from their father’s town, a metal fence has separated their family for seven years.

Like them, millions of children are living with the reality of being stuck between two worlds: what was home then, and what is supposed to be home now. Some cope well, while many others are unable to find an outlet to express their feelings.

In 2010, one million children under 18 lived in the U.S. without proper documentation, and about 4.5 million children were born in the country to parents without proper documentation, according to a report by the Pew Research Hispanic Center.

Not every child deals with immigration the same way — and not every child dealing with immigration is an immigrant.

In the case of Giovanna, 9, and Roman, 7, their family was divided between two countries when their father was deported to Mexico.

Their mother, Aurora Armenta, was left alone with 2-year-old Giovanna and Roman on the way when her husband was caught using a fake Social Security card. Armenta and the children are U.S. citizens, but the family never had the money to apply for her husband’s legal residency or work permit, she said.

For about six years the family traveled back and forth every other weekend from Tucson to Nogales, Sonora.

Last October, Armenta moved the family to Nogales, Ariz. Although she and the children are now living in a shelter, where she works as a housemother, this is the only way for Giovanna and Roman to have a close relationship with their father. She wants the children to go to school in the U.S., and to have the opportunities that citizens enjoy.

“They don’t understand it completely,” Armenta said. “Every weekend they ask, ‘Mom are we going to Nogales? Can we go now?’ but every time we go they don’t want to come back.”

While immigration is debated in the halls of Congress, national policy shapes millions of young lives each day. Immigration reform legislation passed the Senate Judiciary Committee in May.

“‘I might be removed or my mom might have been deported’ — those are issues that you can see clinically that are specific to undocumented community and things that we have certainly seen,” said Shoshana Elkins, a clinical therapist who works with children.

Whether the children or their parents do not have documentation, are refugees or seek asylum, immigrant children face similar challenges as they attempt to integrate into a new way of life and new communities.

“One of the bigger factors with immigrants and refugees is just the lack of knowledge of what kind of help is available and how it can actually help to talk to a neutral outside person like a counselor,” said Aaron Grigg, program manager of the Center for Well-Being at the International Rescue Committee of Tucson. IRC works directly with refugee children and their families.

Often, families are hesitant to reach out for help.

“That’s how things are across the board: They tend to not get help until they are forced to, or when things get really really bad,” Grigg said. “When you are talking about undocumented immigrants, the fear is that ‘when I get help from any place that is federally funded or state funded, I’m going to be discovered or deported.’”

Children whose parents are undocumented also deal with the burden of not disclosing what others would consider commonplace information, such as their address, phone number, where their parents work or even their names, for fear of being discovered.

In his 11 years of experience in working with immigrant and refugee children, Grigg said he has learned that immigrant children tend to take more responsibilities at home at an early age.

“The family needs to be able to become financially independent,” Grigg said. “So there is a lot of pressure for them to help support the family financially, but yet they want to get their education.”

Many immigrant children put those pressures on themselves especially if they are the oldest, Grigg said.

Financial responsibility is not the only role of these children at home. Since most children adapt and integrate to the community much faster than their parents, they end up translating for adult family members, driving them around, helping with finances —details of a family’s survival that other children may not know, Grigg said.

Alex, 16, came to the U.S. at the age of 8 with his mother. Both overstayed their visas. He has struggled to understand why he has to stay in this country and said he resented not having the same freedoms as his friends who were legal residents or citizens.

“Everyone invites me to cross to the other side for quinceañeras and parties because it’s more fun,” said Alex, who asked that his last name not be used. “I had to learn to always say no and say that my mother doesn’t let me or I have something to do.”

None of his school friends know about his immigration status, only close family friends, he said. His mother has always been his most important confidant, but he doesn’t always want to tell her what goes through his mind about feeling stuck.

“I tell my mother some things, but not much,” Alex said.

It is common for immigrant children to hide their personal situations from others, said Elkins.

“You are constantly taking your cues externally about how you are supposed to be and act,” Elkins said. “You want a place here, and here, and you really want to figure out language, and you really want to fit in.”

CORRECTION: This post has been updated to correct the spelling of the last name of the program manager of the Center for Well-Being at the International Rescue Committee. As it was correctly rendered elsewhere, he is Aaron Grigg, not Griggs.

During the Institute, students are working journalists supervised by reporters and editors from The New York Times and The Boston Globe. Opportunities for students include reporting, copy editing, photography, Web production, print and Web design, and video journalism. Institute graduates now work at major news organizations, including The Associated Press, The Los Angeles Times, The Washington Post and The New York Times itself, and dozens of midsize news organizations.

During the Institute, students are working journalists supervised by reporters and editors from The New York Times and The Boston Globe. Opportunities for students include reporting, copy editing, photography, Web production, print and Web design, and video journalism. Institute graduates now work at major news organizations, including The Associated Press, The Los Angeles Times, The Washington Post and The New York Times itself, and dozens of midsize news organizations.